One-third of children in the country have limited access to food, World Food Program says.

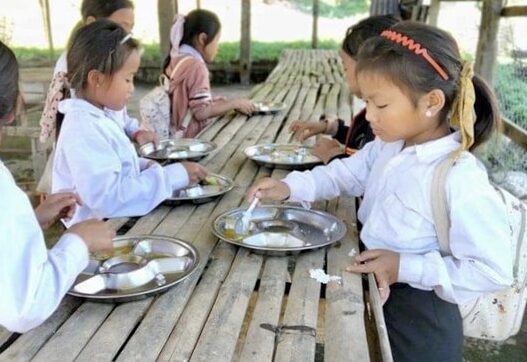

In a file photo, students eating lunch at a school in a remote area of Oudomxay province in northern Laos. Citizen Journalist

Despite economic growth, one-third of Lao children and about 20 percent of the country’s population as a whole continue to experience food insecurity, the World Food Program and Lao government reported.

The WFP said that Laos ranked 87th out of 117 countries on the 2019 Global Hunger Index. Representatives from the group and the government shared the findings after meeting in Vientiane on Jan. 27.

WFP identifies floods, droughts, land degradation, deforestation, relocation and migration as continuing threats to food access in the country.

“While the direct health impacts of the [COVID-19] pandemic have been relatively limited, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic faces an unprecedented challenge with the threat that health, economic and social crises may lead to the reversal of years of progress in poverty alleviation, food security, health and education,” the WFP said.

A study of 20,000 children in the northeastern province of Houaphanh, one of the country’s poorest, showed that about one in five were skinny and stunted and 13 percent were malnourished, an official from the Houaphanh Health Department told RFA’s Lao Service.

“It’s because the families of these children are poor and have no nutritious food to eat. Furthermore, they don’t have access to international food aid programs. … Those are only accessible in two districts of this province,” said the official, who requested anonymity to speak freely without fear of reprisal, like all other unnamed sources in this report.

“Most people including children eat only vegetables, very little meat and fish. Meat or fish is hard to find here,” the official said.

Food shortages are also hitting the Kaleum district in Sekong, another impoverished province in the southeast, a Health Department official there told RFA.

“It’s getting worse. Usually, we rely on food aid coming from Vietnam but now all borders are closed due COVID-19 pandemic. Villagers forage food in the forest and creeks and they grow vegetables,” the Kaleum official said.

“Farmland for growing rice is limited. A lot of land is not arable and not suitable for rice growing. People here eat mostly squash, cucumbers and cabbages. We grow a little rice along the creek. It’s rare for people in this remote area to have a balanced meal,” the official said.

It’s the same story in Xayaburi province’s Xienghone district in the northwest, a Health Department official there said.

“This district is remote and more than 20 percent of children under five are malnourished. Residents don’t have enough food to feed their children. Many children in some villages in the district received food aid three years ago but now all food aid programs have been suspended,” the Xienghone official said.

“Most parents are poor, they work in the mountains every day and leave their children at home with their grandparents who have little food to feed them,” he said.

The villagers don’t have ready access to meat because people typically don’t own livestock: “That’s why they’re still poor and food-insecure,” the Xienghone official said.

Residents in Champassak province’s Khong district raise pigs and chickens, but still do not enough to eat, an Agriculture and Forestry Department official in the province told RFA.

“We still rely on the forest for food, and the food supply is too low. So, we eat whatever we have. We have land, but the land is hot. We can’t grow rice or coffee on it,” he said. “We can only grow a little of rice on the slopes of mountains, but the practice is not productive at all. We have never received any food aid.”

The collapse of a large-scale hydropower dam five years ago had a devastating effect on Champassak and many residents have yet to fully recover, the source said. Thousands of people were forced to relocate when their homes and farms were destroyed in the disaster.

“They were given 261 hectares [644 acres] of farmland, but the land is sandy, not suitable for farming at all,” the official said. “These people really suffer from the chronic lack of food.”

Even when the people have adequate land, they still sometimes cannot grow enough, an official from the Agriculture and Forestry Department of Chonnabouly district in Savannakhet province told RFA.

“They didn’t produce enough food last year because their paddy fields were flooded. They don’t have money to replant rice, buy fertilizer, fuel or seeds. Therefore, they don’t have enough rice, meat and fruit to eat,” he said. “Last year, residents of Chonnabouly District lost 266 hectares of paddy fields to flooding. These people who are already poor are getting poorer.”

Aid organizations working in Laos finger yet another cause to widespread hunger: climate change.

“Flooding and drought occur more frequently, reducing food production and worsening food insecurity. … In the last several years, climate change has been taking a toll on people’s livelihoods,” an aid worker said.

“When it rains, its rains too much, causing flooding and damaging crops. When it’s dry, it’s too dry for a long spell, lowering agricultural production.

“Land is not arable and water shortages, more specifically a lack of irrigation system, is also a problem. So, some years, people have enough food and some years, they don’t,” the aid worker said.

Food Programs Failing

Programs designed to alleviate hunger are not keeping pace with the changing circumstances, a member of another food aid program told RFA.

“People in rural areas are most affected by the failure. The programs haven’t reached the goals because of climate change, natural disasters, land mismanagement. Degraded quality of land, limited farmland, land misallocation and mismanagement make food insecurity worse. More and more farmland has been lost to large development projects. So, Laos still needs food aid,” the aid worker said.

There is some reason to be optimistic. Laos’ economy has grown, despite the pandemic. And aid from the U.S. for a Laos local school lunch program has helped reduce hunger in the country, an education and sports official from Savannakhet province told RFA.

“The U.S. has been supporting the school lunch program in 46 schools in the province since 2016 and the program has helped lower drop-out rate from 4.6 percent in 2016 to 3 percent this year and students have shown more interest in learning,” he said.

“However, the U.S.’ school lunch program will end at the end of June 2022. After that, we’re hoping that the Lao government will continue to fund and run the program.”

You can help donate food by buying a food package here.

Translated by Max Avery. Written in English by Eugene Whong.

Education, Food, Health, Laos, News

Comments RSS Feed