Laos Is On the Brink of Bankruptcy

Luke Hunt yesterday reported in The Diplomat:

“A decade of colossal debt accrual and economic mismanagement by communist authorities in Laos has finally tipped the country towards bankruptcy, with its foreign reserves incapable of meeting its loan obligations without outside help.

Long lines for fuel, rapidly rising food prices, and the inability of households to pay their monthly bills have also led to rare public criticism from around the land-locked country where authorities take a dim view of anyone who disagrees openly with government policies.

It would be too easy to blame China, which accounts for about 47 percent of Laos debt accumulated on the back of major infrastructure project, and its “debt traps,” which have left their mark on countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Fiji.

Nor is the war in Ukraine or the crushing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic an excuse. The chief reason behind Laos’ economic collapse is the perennial thorn in the side of many Asian countries: corruption.

Prime Minister Phankham Viphavanh has admitted as much, telling the National Assembly this week that embezzlement by executives and staff, combined with poor management, are the main reasons for the chronic losses racked-up by 178 state enterprises. The immediate problem is the livelihoods of 7.3 million Laotians who rank among the poorest populations on the planet.”

In a desperate bid to prop up the economy the government is offering about $340 million worth of bonds at a staggering six-month interest rate of 20 percent. Last week Nikkei Asia reported how the debt crisis triggered a rare display of anger against Communist leaders from the Lao public.

“Shortly after a Laotian-language article headlined “Lao economy collapses” appeared on the Facebook page of U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia this month, public rage erupted against leaders of the one-party state.

The 1,100-plus replies to the post include angry rants by Laotians within the landlocked, resource-rich Southeast Asian nation. Despite replies being easily traceable, people have vented. “If the government cannot manage the economy, get out!” fumed one female poster.

This public display of outrage — also evident across other social media platforms including Tik Tok and YouTube — has not been lost on seasoned observers in the Laos capital Vientiane. They see it as a rare sign of courage by a public long cowed into silence by the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party, the communist party in power since the mid-1970s.”

The economic crisis has been brewing over recent months. The signs range from long lines of vehicles at gas stations in Vientiane and beyond to a spike in the price of food and other essentials, as the kip, the local currency weakened against the dollar.

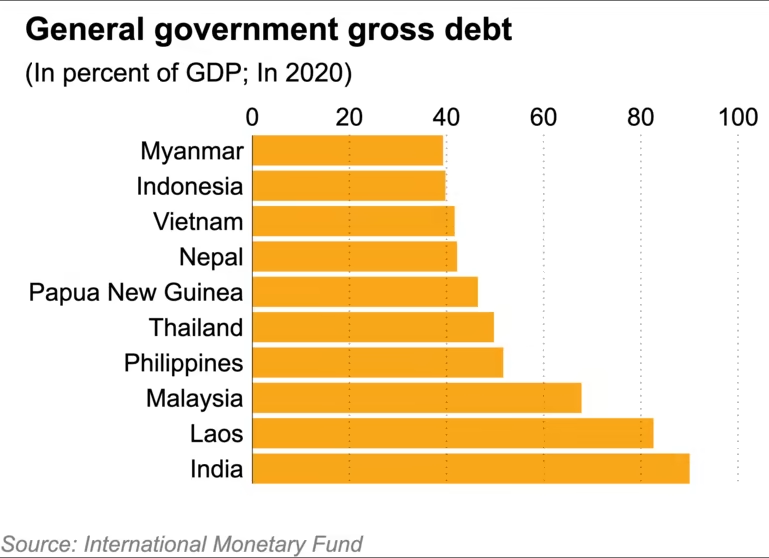

Laos has some of the highest levels of debt in Asia

Ordinary Laotians are angry. The communist government, which offered relatively little financial assistance to people during the pandemic, has blustered. Phankham’s cabinet is perceived as having acted too slowly; it only created a special economic task force on June 6, for instance. It’s also accused of badly communicating the crisis to the public.

Taking their place were some rising technocrats. Malaithong Kommasith, formerly president of the State Audit Organization, will become the new Minister of Industry and Commerce. Foreign-educated, Malaithong was head of the Economic Advisory Team and secretary to the prime minister under Thongloun Sisoulith. He seems a trusted pair of hands within the government apparatus, although is rarely on the political frontlines; he had less than a year of experience as deputy governor Champasak Province between 2020 and 2021. Coming in as the new central bank governor is Bounleua Sinxayvoravong, the former deputy minister of finance. Days earlier, Phankham also announced the formation of a special task force to tackle the country’s main economic problems. It is chaired by Sonexay Siphandone, a deputy prime minister and son of LPRP power broker Khamtay Siphandone. Before the party’s National Congress last year, some expected Sonexay to become the next prime minister.

Laos works on five-year plans, a prime minister’s national agenda is usually reviewed by the party and National Assembly at the end of their spell in office. Any cabinet minister can wait until the end of the term to reveal if the major targets were achieved and leave without having to deal with the consequences.

Experts have been warning about chronic debt for the past decade, yet all Laotian politics seem to do is take on ever more risky loans from China and promise piddling policies to increase tax revenue and stop officials from driving state-provided cars.

This begs a question, though. Can a Laotian politician actually have that much of an impact? Thongloun, the previous prime minister, burst onto the scene in 2016 with grand promises to tackle corruption and party discipline and to balance the books. For some time, he appeared to be doing a good job. And he seemed like a new sort of leader for Laos; open, humble, and sometimes even humorous. But all that petered away. Laos actually fell 14 places in the Corruption Perceptions Index between 2016 and 2020. The national debt surged. After Thongloun was elevated to party chief last year, his predecessor, Bounnhang Vorachit, warned that reform was needed if the party wanted to remain relevant.

Take corruption. It’s almost certain that Phankham’s government will now double down on promises to tackle graft, just as every other administration has done. It’s a potential crowd-pleaser if done well. But successes have been far and few between in recent years. Whereas neighboring Vietnam’s “burning furnace” anti-corruption campaign has taken down billionaires and ministers since 2016, the Lao government spends much of its time talking about stopping officials from using state-funded cars. The fact that Thongloun promised this when he entered office in 2016 and it was dusted off by Phankham last year shows that not much happened over those five years.”

Comments RSS Feed